|

Since ancient times, the human drive to create and listen to music has spanned cultures. Despite the fact that music is not considered an adaptive behaviour nor a second order conditioned stimulus many people consider it to be a significant part of their life. Music is a unique stimulus in that it activates almost every cognitive system in the brain [1]. After music is transduced by the ear and processed by the auditory cortex, signals are sent to multiple areas in the brain, such as the hippocampus and frontal lobe systems which are important for memory, the amygdala which is important for emotion, the cerebellar systems for motor control, and many more [2]. However, listening to music is not simply a passive activity, it can actually change the brain. Studies of early music exposure in developing children, and from the clinical use of music as a treatment for patients with neurodegenerative diseases, brain trauma, or affective mood disorders for example are widely known [3]. Furthering the study of music and the brain may be able to provide insights into a wide range of motor, sensory and cognitive functions, the spectrum of musical capabilities, and non-invasive therapeutic applications.

|

Table of Contents |

Absolute Pitch and Autism

main article: Absolute Pitch and Autism

author: Minhee (Agnes) Park

|

| Absolute Pitch has been frequently reported in people with autism. |

It has been frequently reported in people with sensory and developmental disabilities, including Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Williams syndrome, and congenital blindness[1], that they possess absolute pitch (AP), the ability to identify the absolute frequency of a pitch without any external sources of reference. AP has been found to be prevalent especially among those with ASD, with the likelihood as high as 5%[2]. Researchers have tried to look for the correlations between AP and ASD by investigating the neuroanatomical and cognitive aspects. One of the key topics has been the atypical asymmetry of planum temporale (PT) that might be behind the link between AP possessors and developmental disabilities, but more work on the underlying correlations needs to be done in the future.

Emotional Processing of Music

main article: Emotional Processing of Music

author: Sarah Barnett Burns

|

| Remember, information is not knowledge; knowledge is not wisdom; wisdom is not truth; truth is not beauty; beauty is not love; love is not music; music is the best. – Frank Zappa |

The power music has to elicit emotional responses has spanned human history and cultures. Indeed the emotional nature of music may be its most defining feature [1]. It is the most common reason people cite when asked why they listen to music [2] (Figure 1), and even young children have an innate ability to accurately describe the intended emotional content in musical pieces [2]. However the mechanisms behind the surprisingly strong emotions that music can elicit have been a mystery. A mystery that many philosophers and scientists from Aristotle to Darwin have speculated about [3]. Because music does not have an obviously biological or adaptive role it is unclear what elements would be responsible for the strong and seemingly universal effects it has on the brain, the body and behaviour [3]. Some philosophers have said that it must simply be an "auditory cheescake" - an accident of evolution [1]. However, with recent advances in neural imaging it has been possible to show that music can indeed activate the areas of the brain that are known to be involved in emotions, rewards and core adaptive drives: the limbic, paralimbic and mesolimbic regions [4]. It is therefore starting to become clear how the different elements and structures in music combine to activate these ancient areas in the brain and cause the strong emotional and physiological responses that almost everyone is familiar with.

| Bobby McFerrin demonstrates how well people intrinsically understand the hemitonic pentatonic scale. source: http://www.ted.com/talks/bobby_mcferrin_hacks_your_brain_with_music.html |

Music & Alzheimer's Disease

main article: Music & Alzheimer's Disease

author: Zahra Emami

| Alzheimer's & Music |

|

| Looking at the impact of music in Alzheimer's |

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions worldwide and is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive functions, including the distinctive hallmark of deterioration of memory. Although the medial temporal lobes are a primary targeted brain area in this disease [1], it has been found that in even moderate to severe Alzheimer’s musical semantic and procedural memory, which are thought to involve the left temporal gyri[2], are often preserved [1][3]. This inexplicable conservation of musical memory, coupled with the relatively poor tactics of treatments currently offered, make this wide-spread and impactful disorder a possible candidate for novel therapeutic strategies. Music therapy seems to be a promising alternative, offered in a variety of forms, providing a low cost and low risk approach for the possible prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s, while perhaps also providing insight into the neural correlates of musical memory.

Music Therapy & Mood Disorders

main article: Music Therapy & Mood Disorders

author: Rina Baba

| Music Therapy & Mood Disorders |

|

| Image Source: http://music.colorado.edu/departments/amrc/your-brain-needs-music/ |

Introduction

The benefits of music use on mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, have long been studied across many experiments due to the effects it can have on cognitive, sensorimotor, and emotional processing [1]. Recent experiments that study the effects of music in those with pre-existing disorders show that in fact, music can improve the quality of lives of those with pre-existing depression by decreasing levels of depression and anxiety [1]. Studies conducted on those with other pre-existing neurological diseases such as Parkinson Disease also reflect an improvement in overall quality of life when physical rehabilitation is combined with music therapy [2]. Research on music therapy is therefore currently a relevant field study, as it can open up a field of non-invasive, non-medicinal form of therapy [3].

Music Training on Motor and Cognitive Development

main article: Music Training on Motor and Cognitive Development

author: Kenneth Nguyen

| Music training |

|

| Active music and its impact on the developing brain |

Music, both in its passive and active form, is known to be a stimulus for inducing brain plasticity. Whereas passively taking in music focuses mainly on the auditory cortex, actively production of music (ie. musical training) is much more complex and involves the development of higher-order motor and cognitive regions [1] [2]. Although the molecular mechanism of brain plasticity has been understood as a balance between LTP and LTD events, recent endeavors focus on identifying areas undergoing plasticity as a result of musical training. The wide variety of musical instruments allows for the development of many specific brain regions, despite this, there are overlapping areas which are altered. These areas are considered the main structural changes and the degree to which they change reflects in our behavioral outputs over various domains. The field of music and the brain is rapidly evolving as it is a novel example of experience-dependent plasticity to explore how much of our development is caused by nurture as opposed to nature (genetics) [1].

Neuroanatomy of Absolute Pitch

main article: Neuroanatomy of Absolute Pitch

author: Anthony Chau

| Absolute Pitch |

|

| AP vs. RP on notes recognition |

Absolute pitch (AP) or more commonly known as perfect pitch is a rare ability to recognize any musical note without an external reference. [Bibliography item example1 not found.] Research into this ability began in the 19th century, focusing on 2 main areas, the neuroanatomy and functionality of Absolute pitch. For many years, planum temporale was believed to be the key area responsible for possession of absolute. However, recent study discovered that absolute pitch can also be identified by expansion of right Heschl’s gyrus. [Bibliography item example1 not found.] This discovery not only provides one more viable method for identifying individuals that possesses the absolute pitch,but it also highlights the role of the right hemisphere regarding this skill. [Bibliography item example1 not found.] With the presence of these indicators, researchers suggested that this skill is primarily responsible for infants to acquire their mother tongue during the early stage of development, but is retained due to the lack of development in planum temporale [Bibliography item example2 not found.]

The Association Between Language and Music Processing

main article: The Association Between Language and Music Processing

author: William Chong

| Language and Music in the Brain |

| Exploring the effects of Music on speech production in the brain |

Language is one major aspect that interacts with the human brain daily. It provides itself as a cognitive function to humans. Without language processing, humans would lose a sense of communication and understanding with each other. Language is composed of different levels of syntax, tones, and acoustic parameters. Thus, it is important to understand how the brain perceives language, where it is processed and how to enhance it. Strictly speaking, language processing today has been stated to involve brain regions such as the Broca’s and Wernicke’s area[1]. On the other hand, current research has suggested that music is one effective way to enhance certain language processing such as speech production. Music is much like language where it involves parameters such as intensity, pitch and frequency placed on each note. Moreover, music processing has similar brain region localization to those of language processing. In other words, the activation of brain regions when exposed to music may function to help when it comes to language processing. Therefore, it is crucial to underlie how music expertise may help to enhance language processing such as speech production using a comparative approach with music.

The Perception of Musical Rhythm

main article: The Perception of Musical Rhythm

author: Meishan Yan

|

| Source: 5D Media & Design, 2011 |

The perception of musical rhythm is extremely complex, involving a lot more than just the auditory cortex. Using neuroimaging techniques and behavioural testing, researcher have begun to examine many facets of rhythm processing, including the neural correlates involved in rhythm perception, the developmentally- and culturally-driven changes in rhythm perception, and the limitations and errors that can occur during rhythmic processing. Using functional neuroimaging, the main brain regions correlated to rhythm perception are the cerebellum, the olivary nuclei of the pons, the prefrontal and parietal cortices[1]. Behavioural studies done in infants show that the ability to perceive rhythmic patterns appears extremely early, but babies show fundamental differences in the cognitive strategies employed during musical rhythm processing[2,3]. The early emergence of rhythm perception in infants fuels the controversial question of whether musical rhythm perception is an evolutionary trait (e.g. a byproduct of a more critical process, like the circadian clock or linguistic rhythmicity) or just a neural fluke[4]. Much of the scientific evidence suggests that musical rhythm processing is indeed a part of a much bigger and crucial process, namely language processing and generation. Thus, the perception of rhythm is not limited to being merely a component of musicality, which enables you to be able to enjoy music, but the inability to perceive rhythm may spell consequences in the linguistic domains as well.

The Role of Music Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation

main article: The Role of Music Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation

author: Joshua Gnanasegaram

| Music therapy |

|

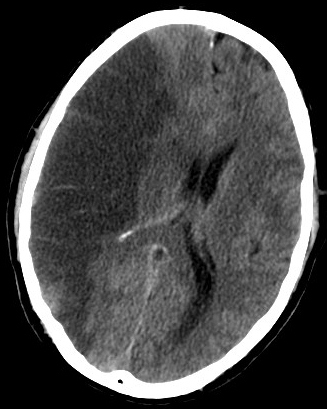

As the debilitating effects of stroke are becoming more cause for concern, therapists have been looking for an effective method through which stroke patients can be rehabilitated. Strokes occur as a result of an interruption of blood flow in the brain, leading to a sudden decrease of brain function. They can be classified into two main categories, hemorrhagic and ischemic [1]. In an ischemic stroke, blood flow is halted or disrupted to certain brain areas due to numerous reasons, such as a clot or obstruction in the arteries. The lack of blood to these areas starves the neurons of oxygen, glucose, and other vital metabolites that are necessary in order for them to function. A hemorrhagic stroke is caused when a blood vessel (such as an aneurysm) bursts and causes blood to accumulate in the brain and cause intracranial pressure(click here for a video module). Depending on where the rupture occurs, a patient with hemorrhagic stroke can present with specific symptoms [2]. Strokes that affect the left cerebral hemisphere can impact speech function and motor and sensory deficits for the right side of the body, while strokes in the right hemisphere can cause hemineglect (on the left side of the body) and depth perception. Strokes are not limited to the cerebral hemispheres, however, such that strokes in the cerebellum affect motor coordination and strokes in the brainstem affect basic functions [3].

| CT scan |

|

| The darkened region on the left shows the extent of the damage from an ischemic stroke |

Due to the widespread damaging effects, rehabilitation is often an extensive, gruelling process for a stroke patient. Professionals from various disciplines often collaborate to help return a patient as much as possible to normal life. Stroke victims may undergo any or all of the three common types of therapy: physical therapy, in which certain exercises and procedures allow a patient to recover lost physical function [4]; occupational therapy, which allows patients to re-learn and develop the skills that are essential to maintain daily living and social interactions [5]; speech-language pathology therapy which re-trains patients that have lost communication and/or swallowing skills as a result of the stroke [6]. Music was used informally while treating the veterans after the first and second World Wars; it has since then become an increasingly recognized form of therapy. While the “healing” properties of music have been discussed for centuries, it was only with the advent of brain imaging techniques that the scientific community began to take interest in this field [7]. As more research is being conducted to explore the effectiveness of music therapy, a more diverse and proactive therapeutic program can be used to help rehabilitate stroke victims.

Tone Deafness – A Neurological Disorder

main article: Tone Deafness – A Neurological Disorder

author: Robert Kosalka

| Tone Deafness |

|

| Anatomy of the tone deaf brain. Image source:http://musicpsychology.co.uk |

Tone deafness, also known as amusia, is a neurological disorder which mainly affects the processing of pitch. This disorder also involves a decrease in recognition of melodies as well as a decrease of recognition of tunes. Studies suggest that amusic individuals have limitations in the discernment of speech spatial perception and the processing of new stimuli. [1] There are two main types of tone deafness, congenital and acquired amusia. Congenital amusia is identified by anomalous brain activity, structures, or connections which occur naturally in the person. [2] Acquired amusia, alternatively, is tone deafness which occurs after an injury to the brain. [1] Studying both congenital and acquired amusia and the underlying anatomical abnormalities reveals the areas of the brain that are used to process the various aspects of music. Different areas of the brain are used to process pitch and rhythm. The study of amusia can greatly improve the anatomical knowledge of music processing. To diagnose tone deafness, a variety of tests are used by the labs involving the ability of the subject to discriminate pitches. One test developed to standardize the process is called the Montreal Battery of Evaluation of Amusias (MBEA). [1] A method of rehabilitation for tone-deaf subjects was developed based on computer assisted repetitive melody discrimination tasks. [3]

Hey guys/friends? Sure friends :D

I think your topic was really cool and innovative and interesting. This was one of my favourite ones to read!